Standard-Essential Patents (Seps)

As is known, a standard is a document that sets out requirements for a specific item, material, component, system or service, or describes in detail a particular method or procedure.

Standards are generally set by Standard-Setting Organizations (SSOs), such as the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) or the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), to name just two.

There are thousands of standards. ETSI alone has set more than 6500 standards. These include the second generation or “2G” (GSM/GPRS), third generation or “3G” (UMTS), and fourth generation or “4G” (LTE) telecommunications standards. For example, a modern laptop computer implements around 251 interoperability standards.

Standards frequently make reference to technologies that are protected by patents. A patent that protects technology essential to a standard is called a standard-essential patent. It is impossible to manufacture standard-compliant products, such as smartphones or tablets, without using technologies covered by one or more SEPs.

SEPs are different from patents that are not essential to a standard (non-SEPs), such as design patents, for example, which protect the design features of an invention. This is because, generally, companies can invent alternative solutions that do not infringe a non-SEP (whereas they cannot design around a SEP). For example, the “slide to unlock” technology is covered by a non-SEP. Most smartphone manufacturers were able to develop different technologies for unlocking a smartphone screen which do not infringe the “slide to unlock” patent. This would not have been possible in the case of a SEP.

There are thousands of SEPs reading on technologies implemented in various standards set by the SSOs. For example, the total number of SEPs declared to ETSI is 155,474. More than 23,500 patents have been declared essential to the GSM and the “3G” or UMTS standards developed by ETSI9. These standards need to be implemented in virtually all smartphones and tablets sold in Europe.

IPR policies of SSOs require patent holders to declare any patents as SEPs that might be essential to standards, without further SSO review of the accuracy of the essentiality declarations. Therefore, even if declarations against specific technical specification documents of the standards are predictors of essentiality, not all SEPs are actually essential – a phenomenon called over-declaration, and the current declaration practices fail to convey reliable information on the essentiality of declared patents.

Since SSOs fail to conduct essentiality checks, disputes whether or not a patent really claims an invention reading on a particular standard have to be solved before entering or during bilateral negotiations (where the parties may typically produce and argue over claim charts, where claimed features are mapped to corresponding product features and, possibly, standard features). Ultimately, only a court may decide whether a patent is essential or not for a particular implementation of a standard and for a particular application of this standard in a specific product.

Therefore, by no means SEP declarations are to be understood as evidence of actual essentiality of the asserted SEPs, and essentiality checks for the asserted SEPs are to be carried out before entering or during any licensing negotiations.

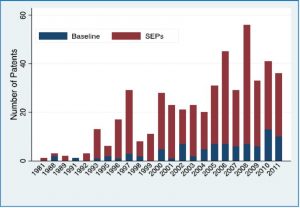

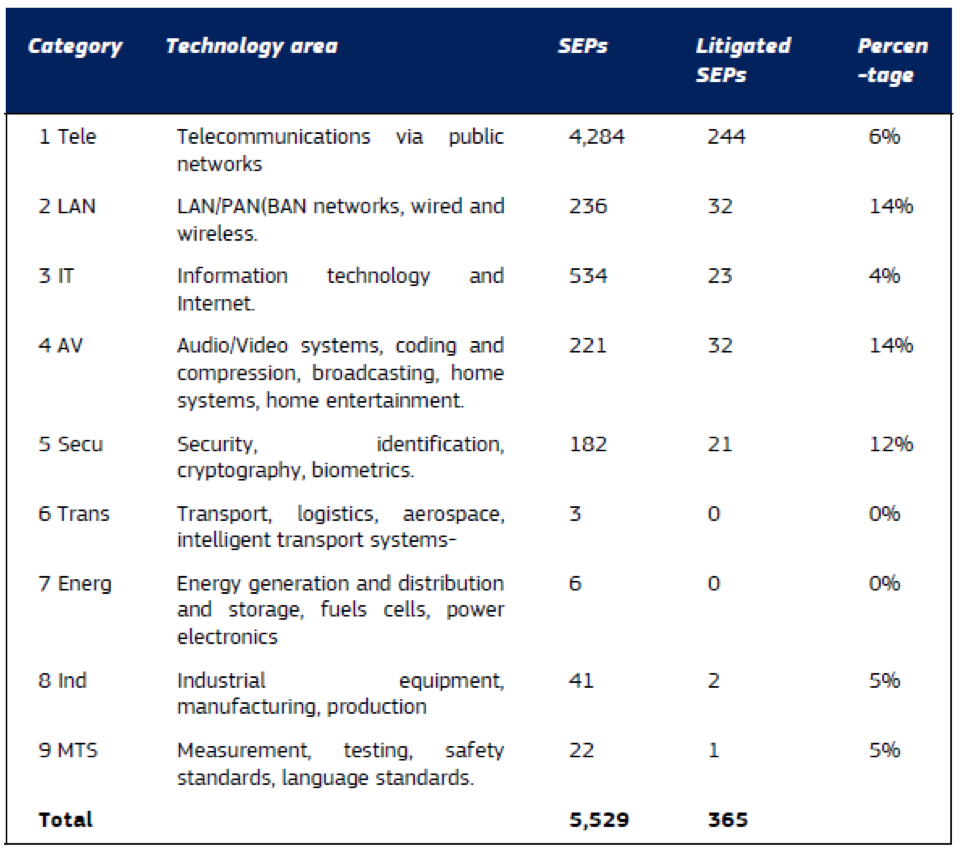

Given their essentiality to standards, SEPs are important for companies. They are also litigated more often than non-SEPs. As the graph below shows, where the number of litigation cases of SEPs and non-SEPs (“Baseline”) are shown by litigation years, the frequency of patent litigation in general, and related to SEPs in particular, has increased considerably over the past 30 years. In the telecommunications sector, there was a noticeable surge in high profile patent litigation involving many important industry players such as Apple, Motorola, Samsung, Google and Microsoft. But as shown in the table below, litigation based on SEPs also happens in many other industries.

Standard-setting (or standardisation) is generally achieved by means of an agreement between undertakings, often competing on the same market, and so is subject to Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). Given their positive economic effects, standardisation agreements are generally compatible with Article 101 TFEU, even if they are agreements between competitors to adopt a single technology in favour of others.

SEPs can, however, confer significant market power on their holders. Once a standard has been agreed and industry players have invested heavily in standard-compliant products, the market is de facto locked into both the standard and the relevant SEPs.

This gives companies the potential to behave in anti-competitive ways, for example by “holding up” users after the adoption of the standard by excluding competitors from the market, extracting excessive royalty fees, setting cross-licence terms which the licensee would not otherwise agree to, or forcing the licensee to give up their invalidity or non-infringement claims against SEPs.

To alleviate these competition concerns and to ensure that the benefits of standardisation are promulgated, companies owning patents that are essential to implement a standard are required by many SSOs to commit to licensing their SEPs on FRAND terms.

FRAND commitments are designed to (i) ensure that the technology incorporated in a standard is accessible to the manufacturers of standard-compliant products, and (ii) reward SEPs holders financially.

The European Commission has issued guidelines on how the TFEU’s antitrust rules apply to “horizontal” agreements between competitors (the Horizontal Guidelines), and in the past has dealt with competition concerns arising from standardisation in cases such as Rambus and IPCom.

In particular, Rambus was preliminarily found to have engaged in a so-called “patent ambush”, by intentionally concealing that it had SEPs, and by subsequently charging royalties for those SEPs that it would not have been able to charge absent its conduct. Following the European Commission’s Statement of Objections, Rambus committed to putting a worldwide cap on its royalty rates for products compliant with the relevant standards for a period of five years. In 2009, the Commission adopted an Article 9 decision, rendering Rambus’ commitments legally binding.

In 2007, IPCom acquired from Bosch a number of FRAND-encumbered SEPs. It was alleged that IPCom violated its predecessor’s FRAND commitment. Following a European Commission investigation, IPCom declared its willingness to conform to Bosch’s.

In the Google/Motorola Mobility merger decision, the European Commission identified the concern that injunctions could be used anti-competitively to exclude competing products from the market or to impose onerous licensing terms, even if licensees are willing to take a licence on FRAND terms.

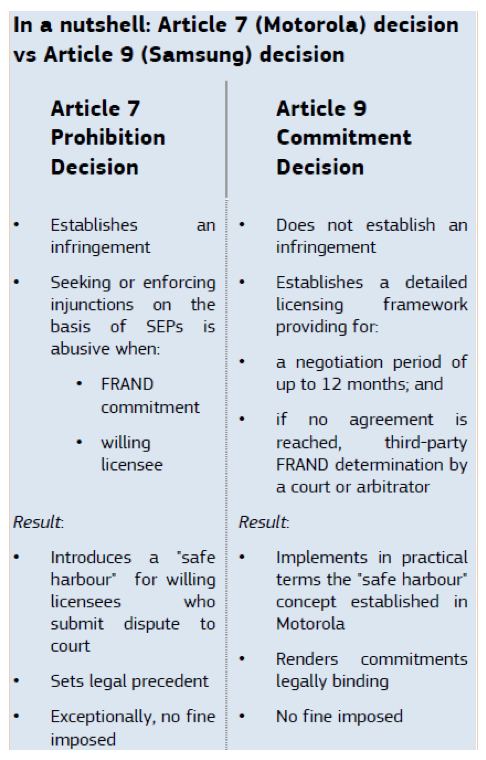

More recent European Commission’s decisions, Motorola and Samsung, also concern the seeking of injunctions on the basis of SEPs. The European Commission considers that seeking injunctions is generally a legitimate remedy against a patent infringer.

However, if the SEP holder has a dominant position and has given a commitment to licence on FRAND terms, then it expects to be remunerated for its SEPs through licensing revenue rather than by using these patents to seek to exclude others. Therefore, seeking an injunction before national courts based on SEPs against a licensee willing to pay for the SEPs was found to constitute abuse of a dominant position.

The telecommunications industry has recently seen a significant increase in costly patent litigations which some commentators have called “smartphone patent wars”.

In 2012, following the grant of an injunction (based on one SEP) by a German court, Motorola enforced the injunction in the German market. The enforcement led to a temporary ban on Apple’s online sales of iPhones and iPads to consumers in Germany. In addition, following the enforcement of the injunction, Apple was forced to enter into an onerous Settlement Agreement with Motorola whereby Apple had to give up its invalidity and non-infringement claims. This, in practical terms, may have forced Apple to pay for invalid and non-infringed patents (also for the past). Moreover, it is in the public interest that potentially invalid and non-infringed patents can be challenged in court and that companies, and ultimately consumers, are not obliged to pay for patents that are not infringed.

In the Motorola case, the European Commission found an infringement of the EU competition rules in Motorola’s seeking and enforcement of injunctions against a willing licensee, Apple, based on one of Motorola’s SEPs. The European Commission reached this conclusion in view of the specific factors distinguishing this case from a “normal” case in which a patent holder seeks an injunction. First, Motorola had declared the patent on which it sought the injunction essential to the implementation of the 2G ETSI standard. Second, Motorola committed to license the SEP to third parties on FRAND terms. Third, Apple agreed with Motorola that in case of dispute the German courts would set the applicable FRAND rate and Apple would pay royalties accordingly.

The Motorola decision establishes that the agreement of a potential licensee to a judicial setting of a FRAND rate in case of dispute is a clear indication of its willingness to enter into a licence agreement and to pay adequate compensation to the SEP holder. Thus there is no need or justification for a SEP holder to have recourse to an injunction to protect its commercial interests. In this particular case, the seeking and enforcement of an injunction caused Apple to renounce its legitimate rights to challenge the validity and infringement of Motorola’s SEPs. There is a strong public interest in fostering challenges of patent validity and infringement. Royalty payments for SEPs which are either invalid or not used may unduly increase production costs, which in turn may lead to higher prices for consumers.

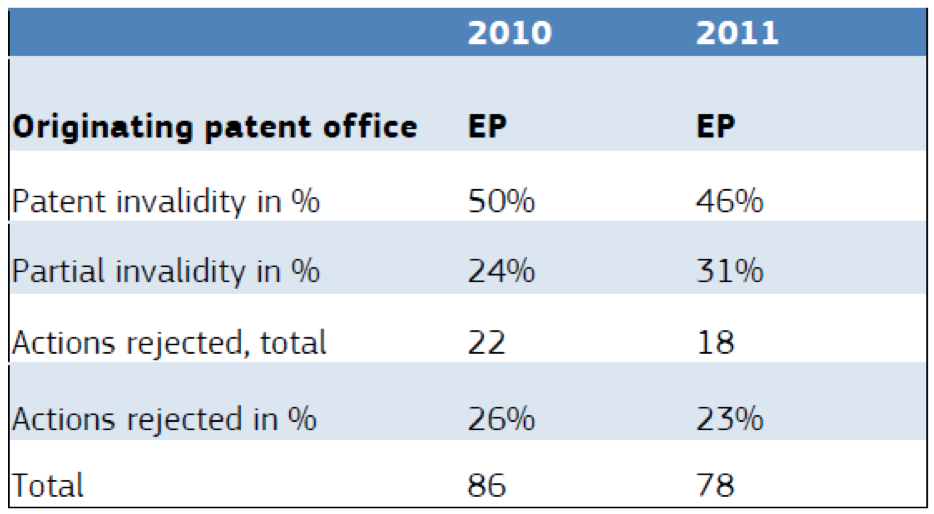

On average more than 30% of European invalidity actions result in the explicit invalidation of the challenged patents, and approximately 50% of the patents challenged are found not to be infringed.

Table below shows the invalidity rates before the German Federal Patent Court.

In the Samsung case, the alleged infringement consisted of the seeking of injunctions against a willing licensee, Apple, before the German, Italian, Dutch, UK and French courts, aiming at banning certain Apple products from the market on the basis of several Samsung 3G SEPs which it had committed to license on FRAND terms.

As a result of the European Commission’s investigation, Samsung committed to not seek injunctions in Europe on the basis of SEPs for mobile devices for a period of five years against any potential licensee of these SEPs who agrees to accept a specific licensing framework. This licensing framework consists of a mandatory negotiation period of up to 12 months, and if the negotiation fails, third party determination of FRAND terms by either a court, if one party chooses, or arbitration if both parties agree. The commitments make it clear that, if the parties raise concerns about the validity or infringement of the licensed SEPs, the judges or arbitrators will have to take those into consideration.

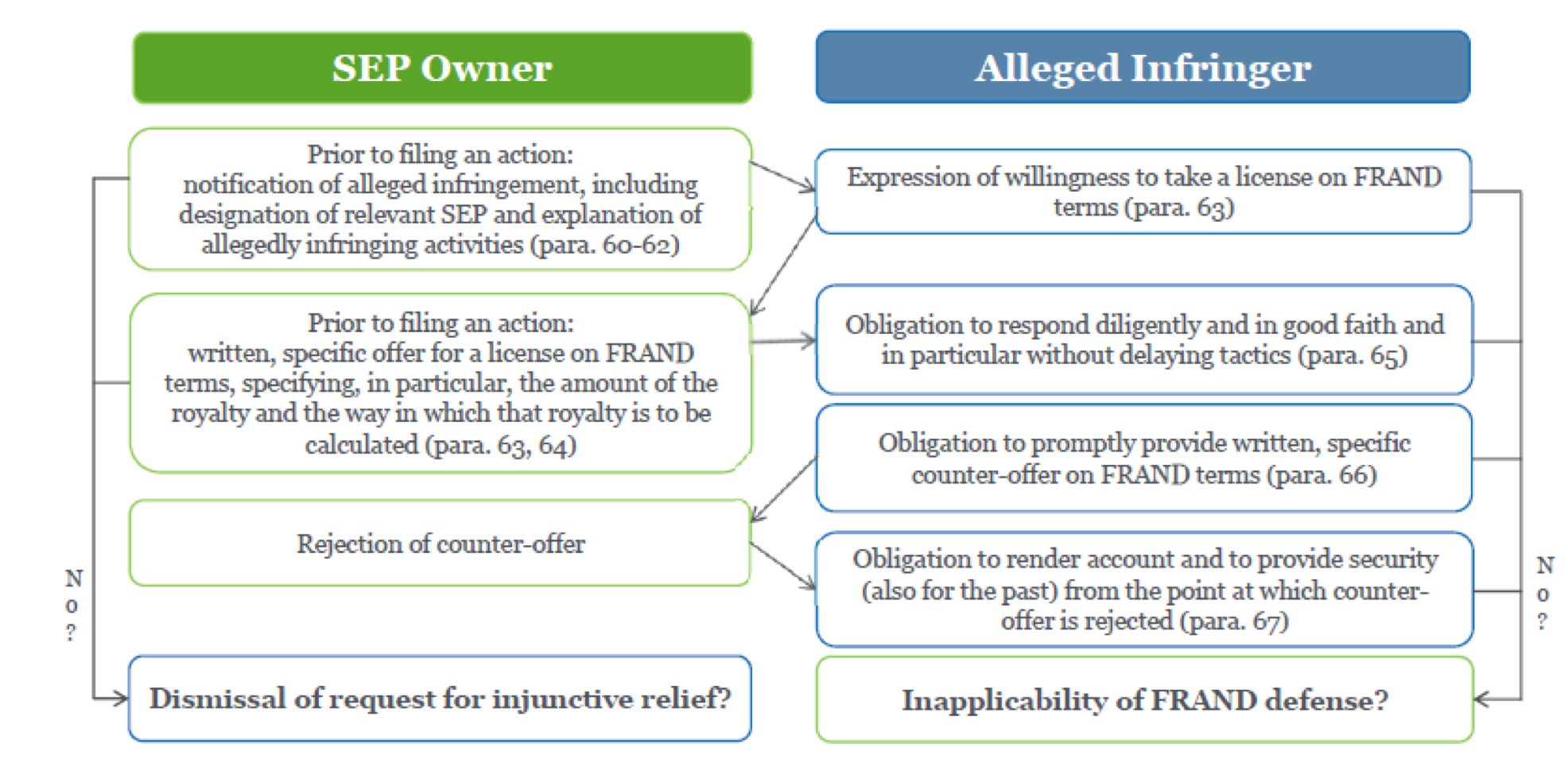

A recent judgment of the European Court of Justice (CJEU) in Huawei vs. ZTE has provided valuable guidance on the circumstances when a SEP holder that has committed to license its SEPs on FRAND terms is entitled to seek an injunction against an Implementer (i.e. a company that uses the teaching of the SEP) without acting in breach of competition law against abuse of dominance (Article 102 TFEU).

The CJEU’s judgment is again a “middle path” between the interests of SEP holders in protecting the value of their inventions, and those of the Implementers in developing and marketing products that utilize standards. The CJEU’s judgment has set out the following important principles that SEP holders should follow in SEP patent licensing negotiations in order to prevent an application for an injunction being regarded as an abuse of dominance:

- The SEP holder must warn the Implementer in writing of the infringement complained of by noting the relevant SEPs and how they are alleged to be infringed. This is because the Implementer may not necessarily be aware that it is using the teaching of SEPs that are both valid and essential to a standard.

- The Implementer must express a willingness to conclude a licensing agreement on FRAND terms.

- The SEP holder must provide a specific, written offer for a license on FRAND terms. The offer must specify the amount of the royalty and how it is calculated.

- The Implementer must “diligently” respond to that offer, in accordance with recognised commercial practices and in good faith, which must be established on the basis of objective factors and which implies, in particular, that there are no delaying tactics.

- If the Implementer fails to accept the offer made to it, a counter offer that corresponds to FRAND terms must be made promptly and in writing to the SEP holder.

- If the Implementer is using the teachings of the SEPs before a licensing agreement has been concluded, the Implementer must provide appropriate security in respect of its past and future use of the SEPs. For example, a bank guarantee for the payment of royalties or by placing the relevant amount of money on deposit.

- Where an agreement has not been reached on the details of the FRAND terms following the counter-offer by the Implementer, the parties may, by agreement, request that the amount of the royalty be determined by an independent third party.

- The implementer cannot be criticized for challenging, in parallel to negotiations for a grant of license, the validity or the essentiality of the SEPs or for reserving the right to do so in the future. Thus, in contrast to the Orange Book Standard that required an “unconditional offer” to license from the Implementer (meaning agreement not to challenge the alleged infringement or the validity of the patent), the Implementer can defend itself with non-infringement and invalidity arguments.

The above-described protocol, sometimes also referred to as the Huawei vs. ZTE ping-pong match, is depicted below:

In parallel to the licensing negotiation, the alleged infringer may challenge the validity of the SE, challenge the essentiality of the (alleged) SEP, challenge the actual use of the SEP, or reserve the right to do so in the future.

The precedent set by the two European Commission’s decisions in the Motorola and Samsung cases provides a path to “patent peace” in the telecommunications industry. Moreover, these two cases bring legal certainty in all industries where standards and FRAND-encumbered SEPs play a role. They constitute a guide for Member State courts, as well as to SSOs, on the interpretation of EU competition rules regarding the enforcement of FRAND-encumbered SEPs.

The European Commission’s Motorola and Samsung decisions confirm the European Commission’s balanced approach with respect to IP rights and competition. Whilst IP rights are important for innovation and growth, they should not be abused to the detriment of competition and ultimately consumers.

In concrete terms, these decisions clarify that SEP holders should not abuse their market power by “holding up” willing licensees with injunctions. These decisions provide further clarification and guidance to industry on the competition law limitations to SEP-based injunctions.

In particular, in the Samsung and Motorola cases, the Commission clarifies that in the standardisation context, where the SEPs holders have committed to (i) license their SEPs and (ii) do so on fair, reasonable, non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms, it is anti-competitive to seek to exclude competitors from the market by seeking injunctions on the basis of SEPs if the licensee is willing to take a licence on FRAND terms.

In these circumstances, the seeking of injunctions can distort licensing negotiations and lead to unfair licensing terms, with a negative impact on consumer choice and prices.

Mirko Bergadano

© Studio Torta (All rights reserved)